A pupil engaged in skills training at General Piet Joubert School in Limpopo. Photo: Ntokozo Abraham/SAAJP

Special schools that cater for deaf and blind pupils are struggling with massive, rising and erratic electricity bills which are chewing up the grants they should be using for basic equipment.

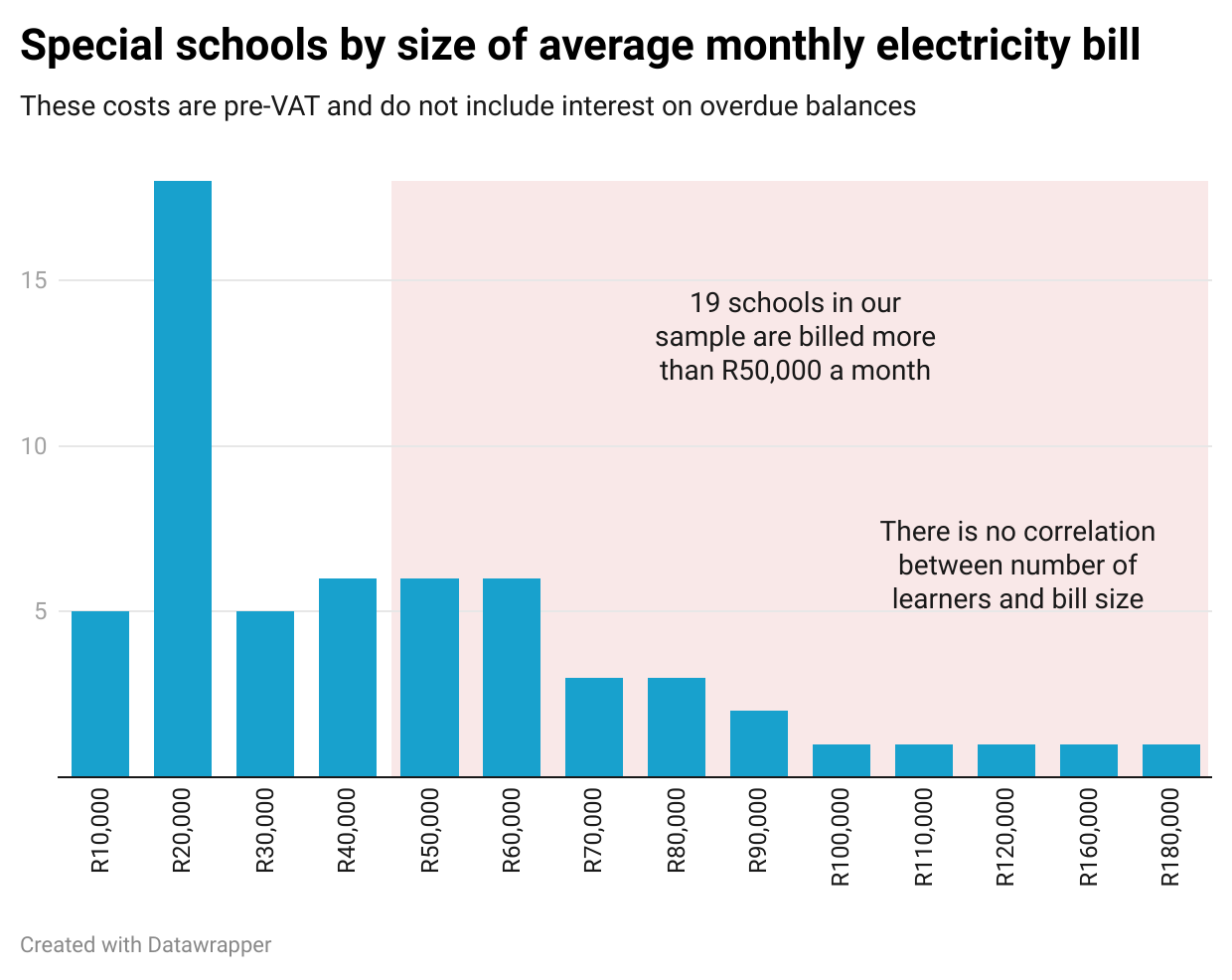

Some of these schools report average monthly electricity bills of R60 000, while at least one [School B on the chart] has bills of over R170 000 for a month. All of them say their bills are impossible to understand, they shoot up without explanation, and service charges (the basic charge just to have electricity delivery to the schools) are sometimes so high that they face crippling bills even during school holidays when the classrooms are empty.

Not even Eskom can explain the amounts being charged. We approached Eskom on July 22, trying to understand these bills, and provided them with account numbers and at least 14 statements of schools with high bills.

Eskom repeatedly sought deadline extensions.

Graphics: Adam Oxford/SAAJP

Now, 46 days later, Eskom spokespersons Daphne Mokwena and Theresa Magubane, said:

“Our sincere apologies for the delay in sending you Eskom’s comment. Our team were still working on a response. Please give us until end of business today to get back to you.”

No response was received by the time of publication.

A media enquiry was also sent to the Polokwane Municipality’s spokesperson, Thipa Selala, on 25 July, which supplies electricity to some schools such as General Piet Joubert Special School.

On 26 August, Selala said, “I will call you back. I am in studio,” No response was received at the time of publishing.

To keep the electricity on, many schools have no alternative but to sacrifice funds designated for Learning and Teaching Support Materials (LTSM) such as the computers and textbooks essential for teaching the deaf, blind and those with other disabilities. This was confirmed by many School Governing Board (SGB) members and the SA National Association for Specialised Education (SANASE).

Laptops are a prerequisite for the education of deaf pupils, as they utilise them to record their videos for their lessons and exam answers for their home language, South African Sign Language (SASL).

Special schools receive an annual grant from the Department of Education of between R1 million and R4 million. Unlike in ordinary schools, this has to buy food, stationary, LTSM resources, infrastructure maintenance, salaries for support staff, SGB members’ activities, transport, communication, computer maintenance, furniture and equipment.

The schools’ outcry is that electricity charges are so high they can eat up most of this grant.

To understand the extent of the problem, we collected 188 bills from 66 schools in six provinces: Limpopo, Northern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal, Eastern Cape, North West, Mpumalanga, Western Cape and Free State. SANASE provided original electricity bills from many schools and additional samples were released by the provincial departments of education in the Free State and North West.

The data sample covered a three-month period from February to April 2025, including the first few weeks of this year’s tariff increase. Bills came from Eskom, municipalities and a private company.

The survey showed that many schools have to pay an average of R60 000 a month, and at least one pays over R170 000.

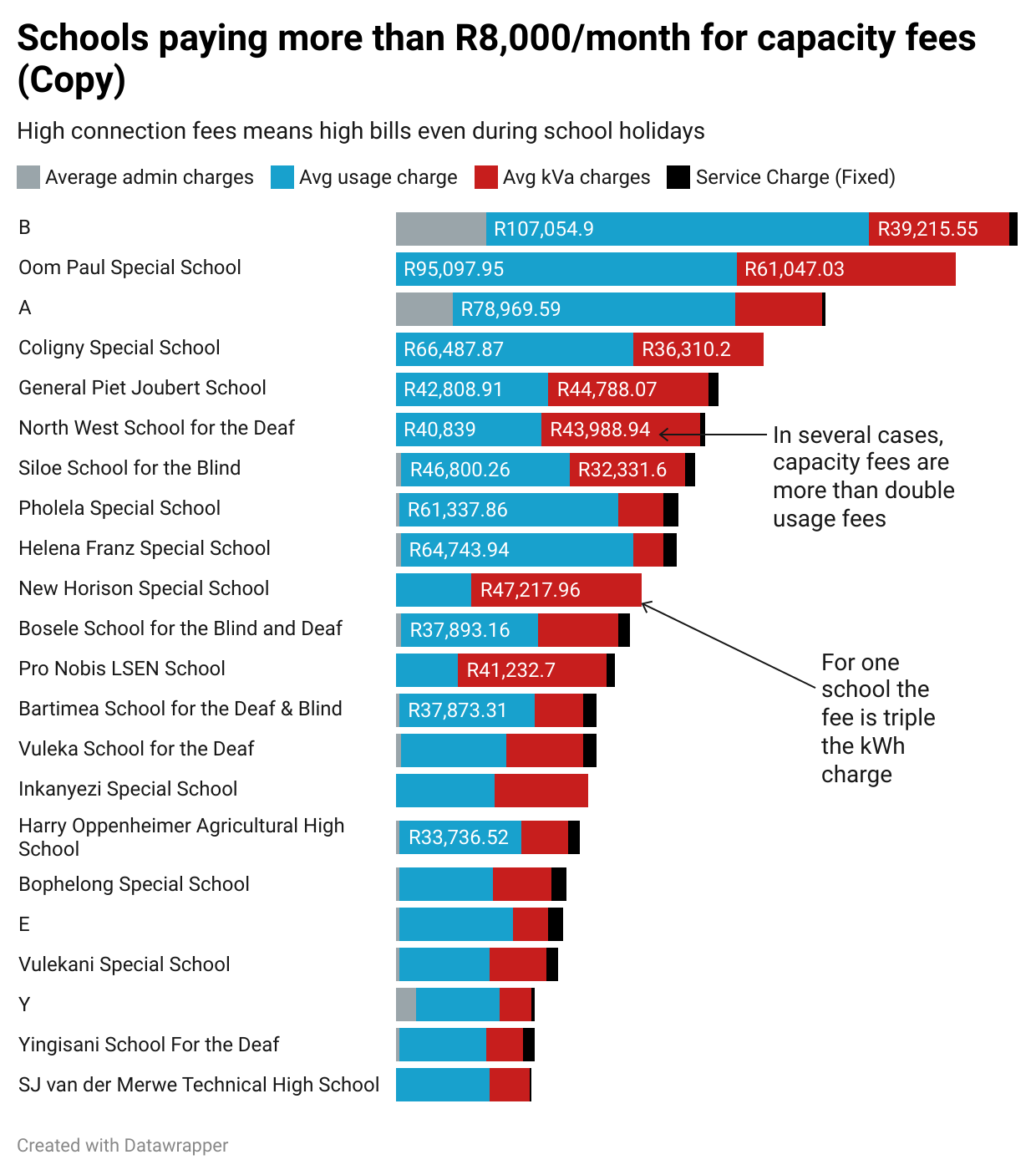

In the Northern Cape, School B’s average monthly bill is R173 590, School A R119 970, Oom Paul Special School R156 140, Coligny Special School R102 800 in North West.

In the North West province, North West School for the Deaf’s

average bill is R86 620.

In Limpopo, General Piet Joubert R90 230, Siloe School for the Blind R83 870, Helena Franz Special School R78 530, New Horizon Special School R68 600 and Bosele School for the Blind and Deaf R65 240.

In KwaZulu-Natal, Pholela Special School has to pay R78 770 per month and VN Naik School for the Deaf R76 790.

Attempts by some of the schools to decrease the cost by using alternative energy sources, such as solar and gas, has proven fruitless, as bills have continued to increase. Concerns are that the charges are high even during long school holidays.

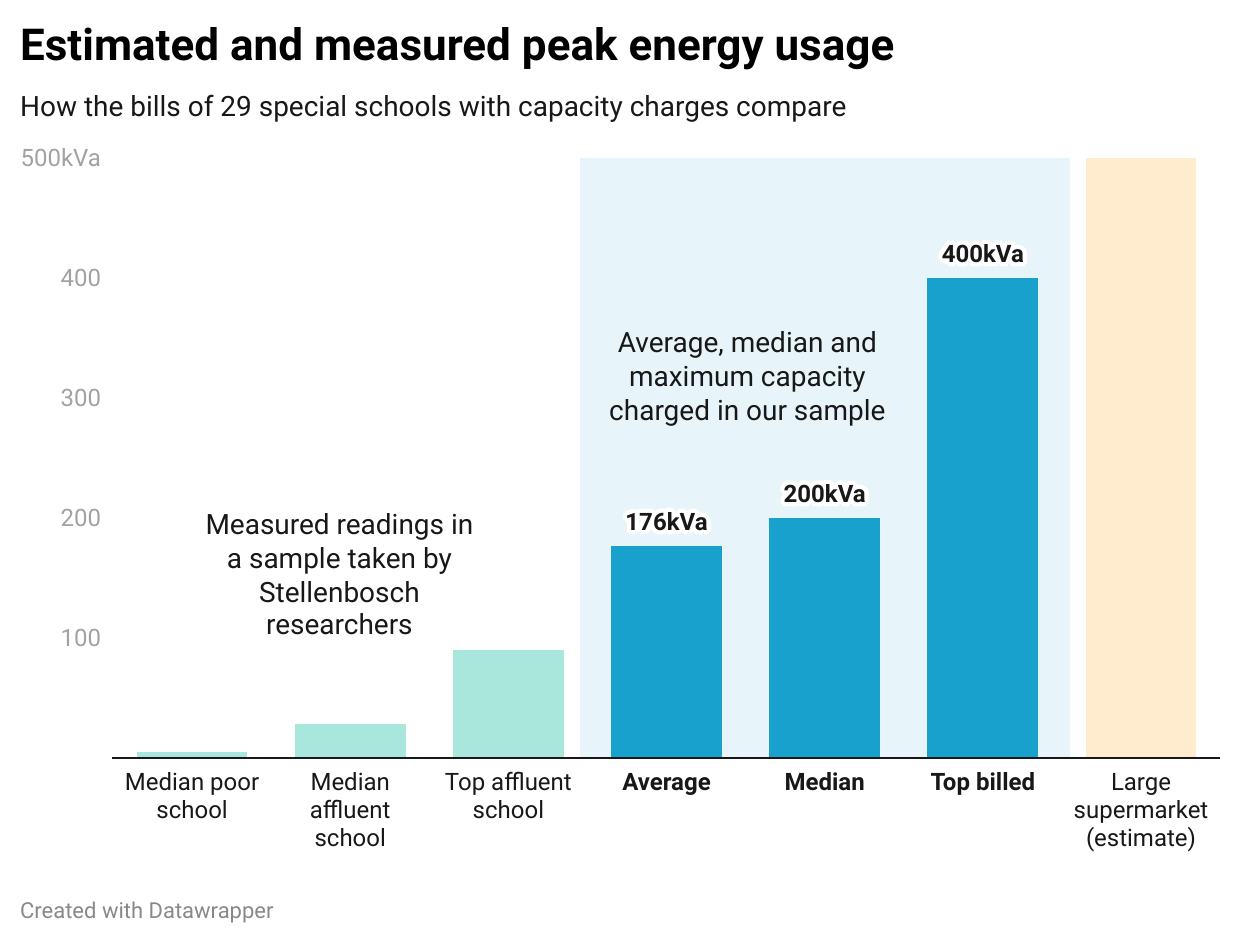

Schools such as Vuleka School for the Deaf, Vulekani Special School, Inkanyezi Special School, Pholela Special School, St Brandens School, Helena Franz Special School, Bosele School for the Blind and Yingisani School for the Deaf in Limpopo, Bophelong Special School in the North West, Bartimea School for the Deaf and Blind School in Free State, and Boitumelo Special School in Northern Cape are charged for the supply of 200kVa-400kVa, though they can only use a fraction of this.

At Bosele school there are 283 pupils, 154 are Deaf and 129 blind. The school has 20 computers in the laboratory utilised by the teachers for deaf pupils. Its average monthly bill for electricity was over R65 000 before the April tariff increases. Statements seen show that in August it received a bill of R96 158.37 - an increase of 47% over its March bill, despite only using 7% more energy in the winter month.

Lesiba Matlaila, an SGB member at Bosele, said that none of the 154 deaf pupils have the essential laptops, a situation mirrored by the 328 deaf pupils at the Durban School for the Deaf in KZN. Vuleka has merely 22 for 278 pupils, leaving 256 pupils without access to laptops. The North West School for the Deaf has 60 deaf pupils and only 21 old laptops. They are struggling to buy new ones due to the R1.2 million debt on their municipal bill, which they are currently querying. The school is being charged an additional R9 000 a month interest on top of its R86 000 average monthly bill.

In the Free State, the education department has remedied the issue by buying laptops for the deaf pupils. Despite this, some of the Free

State schools for children with special needs are often threatened with power

cuts, especially toward exams.

Matlaila remarked:

“If we don’t pay Eskom, the whole school will come to a standstill. There will be no food in the kitchen, no hot water, classes will not function because we need copiers and copiers need electricity. So, we will always prioritise paying Eskom so that they don’t cut us off the system.

“Most of the time, we are unable to procure gadgets for the deaf and blind learners because we have to service the debt that Eskom is billing us, which is very high in our opinion. Even when you engage them, questioning the authenticity of the bill, you will always be surprised by the response you are getting from Eskom. So many plans are affected by the price of the electricity in our schools.”

Matlaila said that during their annual financial planning they include resources for learners, but steep electricity expenses use up most of it.

Matlaila stated:

“When we plan and estimate expenses for all necessary items,

including payments to Eskom, we are always caught by surprise by the exorbitant

bills that will be coming from Eskom. This occurs even during the period of the

year where learners are not at school. For an example during Easter holidays,

the bill can be around R50 000.”

Makhanya Sibiya, SGB chairperson said, “We have 328 learners. Our learners have three disabilities, deaf, autistic and intellectual impaired. Due to strained budget, the school cannot afford to buy for each learner. The water and electricity are now consolidated, but the bill is too high.”

Scelo Madodo, SGB chairperson of Pro Nobis LSEN School for

children with severe intellectually disability in KZN, remarked, “However, we

find ourselves not being able to accommodate all that [spending on LTSM]

because 80% of the money goes towards electricity.

“Some of the children face complex problems, possessing

multiple disabilities. For instance, one child may be hard of hearing, visually

impaired, and cognitively challenged. These children require specialised tools,

such as specific pencils. Those with cerebral palsy may need stretching balls

and other resources, which are part of LTSM, and these necessities are

impacted. At times, the school even runs low on paper, forcing them to draw

resources from the skills section, which consequently affects that area, since

everything is funnelled toward electricity and water costs.”

To compare the bills, we separated them into four categories

of charge: fixed monthly service charges, daily administrative charges, metered

usage (measured in kilowatt hours, or kWh) and peak capacity (measured in

kilovolt amperes, or kVa). Peak capacity charges represent highest expected or

measured usage throughout the month. If a school consistently draws 40kVa from

the grid, but for 30 minutes a month turns on all its geysers, ovens and

cleaning equipment and surges to 100kVa of use, it will be billed for 100kVa.

Graphics: Adam Oxford/SAAJP

Some bills, such as those on Eskom’s basic urban tariffs, do not include kVa charges at all. In many other cases, kVa capacity is fixed at the start of the month rather than measured. Harry Oppenheimer school, for example, paid over R14 000 a month for a 400kVa connection in February, March and April, despite only drawing a maximum of around 126kVa at peak use.

In the April tariff increase, many of Eskom’s kVa tariffs were increased dramatically, especially for those schools like Bosele which have invested in solar and gas to reduce their usage and the impact of loadshedding. Bosele’s peak capacity fees increased by almost 80%, from R24 539 to R43 821 per month.

In an article published in Energy Research & Social

Science, researchers at the University of Stellenbosch, who studied energy

usage in a variety of schools in the Western Cape, discovered that the largest

school in their sample drew a maximum of around 60kVa.

Graphics: Adam Oxford/SAAJP

Many of the statements we studied had left head teachers struggling to interpret how charges were arrived at, and we too found them too confusing to include in our analysis. Several municipalities fail to include meter readings or tariff rates on bills, or in one case failed to provide an invoice at all. Schools such as Masinakane Special school in Mpumalanga are among those that did not get invoice from Eskom. Other bills from municipalities in the Western Cape and North West are written in Afrikaans making it more difficult to understand. Some schools appear to be charged a flat rate for usage with the same estimate every month.

Usage estimates, too, are a serious issue. Several schools in the sample relied on estimated bills for over six months, leading to large corrections for under- and over-payments. School B in Sol Plaatje which has a debt of over R4m to the council because its electricity costs are over R170 000 a month, usage was estimated at what seems to be a flat rate of R107 054 a month, with a connection fee of R41 951. An additional administration charge of over R25 000 is also added on.

Energy expert Chris Yelland said there are procedures to be followed when estimates are done and that schools need to look into whether estimates were done correctly. Usually, he explained, a complex formula is applied to estimate usage, and a recurrent “flat fee” would be highly unusual.

Masinakane Special School allegedly received no bill for October from Eskom. Statements seen show that in November it was R627.93, December R836, January R821.31, February R713,83, March R0.00. In April and May there was allegedly no bill from Eskom, before being hit with a retrospective charge of over R151,749.95 in June, July R19,053.52 and August R28, 949.19.

The President of SANASE, Fanny Mashaphu said, “They [Masinakane] have exceeded their R180 000 budget for this financial year. In August, they took money from the building maintenance budget to pay the Eskom bill. This is because they were scared that Eskom would cut off their electricity. They could not stay without electricity because they have to bake bread and buns for hostel learners and do laundry for them. So, they wouldn’t have left the learners to go to school with dirty clothes. The school bakery is important because it is used to teach learners baking skills.”

Matlaila explained that in Bosele, “The electricity bill surpasses what we budgeted for. For example, monthly, we allocate around R50 000, but come June, we discover the bill is around R80 000.

“Our annual budget is around R3.6 million. Normally we budget around R50 000 a month for electricity, which is around R600 000 or R800 000, but it goes almost to a million rand. Imagine if you pay three R80 000 in three months, in a year that is way above what we have planned for and budgeted for. At some stage, we were billed around R90 000 for a month.”

Matlaila stated that laptops are crucial for their learning because seeing a physical object makes it easier to understand than just a word description.

“When you tell a deaf child that something is red, they need to actually see the colour red on the screen, understand the word, and learn how to use that term as well as recognize that colour,” said Matlaila.

Mashaphu added that, “When teachers ask children to summarise a story, they do not expect a written response in English and Sepedi. They expect summary using Sign Language, which can only be captured through a video recording. The teacher watches the video, assesses the learners, and provides marks. According to the sign language policy, every learner should have access to a laptop, so they can receive questions not as a written script but as a PowerPoint, allowing them to respond in Sign Language through video submissions. This is a critical gap that needs to be filled. For deaf learners, a laptop functions as a pen and paper for sign language. Ideally, every deaf learner should have one, but many schools for the deaf do not have these resources. Without electricity, educators would find it incredibly challenging to equip these schools.”

Mashapu said their concern is not the education department, but the energy suppliers.

South African National Energy Development Institute referred our media enquiry to Ministry of Electricity and Energy, stating they could be conflicted if required by the Ministry to investigate Eskom, municipalities and Centlec.

Based on this investigation and enquiries to Eskom, other energy suppliers and Ministry of Electricity and Energy, Energy Ministry’s spokesperson, Tsakane Khambane, said, “Eskom has been working on a programme for behind the meter solutions to be rolled-out for schools. They will be sharing the project size and scope with us this week. This will ensure that electricity bills for those schools are reduced, enabling schools to redirect that budget for other curriculum priorities whilst using more cleaner sources of electricity.”

By the end of the week, the ministry had not confirmed whether Eskom had shared the project size and scope.

Spokesperson for the Minister of Basic Education Lukhanyo

Vangqa said the department will respond after communicating with all provinces.

Vicky Abraham is an investigative journalist, Ntokozo Abraham, an economic and data journalist of Diary Series of Deaf People (www.thedeafdiary.com) and Adam Oxford a data journalist and founder of Area of Effect (areaofeffect.tv). This investigation is produced by the Southern Africa Accountability Journalism Project (SA | AJP), an initiative of the Henry Nxumalo Foundation with the financial assistance of the European Union. It can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union.